Challenges to creating a Network State

This is a review of the ‘How to Start a New Country’ piece by Balaji S. Srinivasan, which highlights possible pathways to a country founded and built online, and later also owning physical territory. I call this ‘the Reverse Estonia’, as the country has been on a similar path in reverse since the late 1990s. Estonia is increasingly moving government services online, from the ability to start a company completely online to replacing Ambassadors with chatbots.

Human Resources

First of all, why start a new country? In his piece, Balaji rightly compares starting a country to having the opportunity to create something from scratch, maybe correct the wrongs you have previously seen in other countries. He argues that if we had to replace an existing firm rather than start a new company, or if we had to raze a building rather than buy new land, we would have been limited to what we could do. He’s right, that is limiting, and when it comes to countries you are doing just that – moving human resources from one entity to another.

This is not to say it’s impossible to start afresh, without historical baggage, but a new country will be taking away resources from existing ones and when it comes to realpolitik, this is a zero-sum game. The resistance to a newly created digital country, will not come from individuals but states themselves.

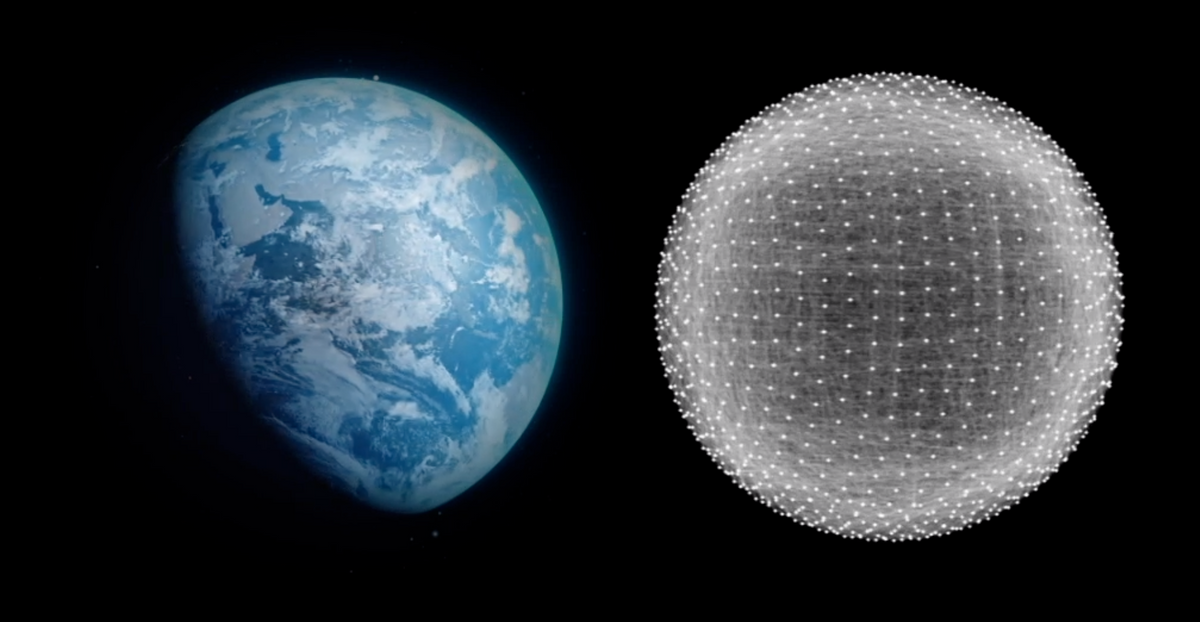

The “brand new”, as Balaji puts its, might be unthinkable to countries, but they know that anything new will still be fighting over the old, over human resources and the wealth humans create. This is the first challenge I foresee when it comes to creating a digital country. Human resources cannot be shared, and more citizens for this digital country, will mean fewer citizens, and therefore less wealth, for other countries. Human resources and how these are managed are what makes a country “real” and investment in humans and their needs – food, education, shelter, is what ultimately allows a country to become richer. Micronations remain so because they have very few human resources to work with and no incentive for people to become citizens of that same micronation. This is also the issue with ‘brain drain’ and the vicious circle it creates for countries with lower standards of living or those not attractive enough for immigrants.

Societal Definition

When it comes to how to start a new country, I’m not sure if seasteading, space, and cloud countries can be considered ways to start a country, as this has not been proven yet. On the other hand, while currently established countries have been founded as a result of armed conflict or through winning elections, this was not an end in itself. One can win an election or a war on the promise to found a new country, but it is going to take much more than that to be able to call your territory, a ‘country’. An example of this is the region of Catalonia, in Spain.

This is where the second challenge in starting a digital country comes in. First of all, there is the problem of defining what the term ‘country’ really means. It seems that here, Balaji is assuming that (1) the societal definition of a country is that of being a member of the United Nations, and (2) that this membership is based on the number of citizens of a country.

As I recently wrote in ‘How to start your own country in four steps‘, there is no universal definition of what ‘country’ really means. Take, for example, the 1933 Montevideo Convention on the Rights and Duties of States, which is one way under the declarative theory of statehood of how proto-states can be recognised as countries. It highlights four qualifications for a country to be considered as such – having a permanent population; a defined territory; a government; and the ability to enter into agreements with other states.

While a “real” proto-country usually has a problem to satisfy the final qualification, the proposed digital country will immediately have an issue with three of the four qualifications – a permanent population settled in one place, a defined territory and borders, as well as the ability to enter into agreements with other states.

Bearing in mind that there are “real” countries on Earth that satisfy all four but still won’t be admitted to the UN, or even recognised by states around the world, the new digital country will have more of an uphill battle to gain recognition and sovereignty, and eventually become part of the United Nations.

UN membership is very much based on relationships between countries, especially with those sitting at the UN Security Council. Let’s say that this new digital country has millions of citizens, billions in financial reserves, and also some territorial holdings. By declaring these territorial holdings as belonging to this independent new country and not to a private individual or a private company, one has already made an enemy of the country that the territory belonged to in the first place. No country will allow another to take away its territory, let alone by a newly set-up country. Take a look at the situation with northern Cyprus, which is the result of an armed incursion. Indeed, every country created in the last century was created with the blessing of world powers, or at least allowed to exist because it did not endanger the status quo. De facto countries like Northern Cyprus and breakaway regions like Transnistria will never be admitted to the UN, as long as regional and world powers do not recognise them as countries.

The number of nationals belonging to a country also does not impact whether an entity is recognised as a country or not. The Sovereign Military Order of Malta, which many consider as a country and have diplomatic relations with, has just 3 official citizens, and there are countless countries, members of the United Nations, with populations in the lower thousands. On the other hand, regions like Somaliland – a stable, democratic, and the richest region in Somalia, with a population of around 3.5 million, is not recognised as a sovereign country by almost all the “real” countries.

Way Forward?

Balaji argues that these challenges can be overcome through economic leverage. He mentions the example of cryptocurrency and Bitcoin, how it was first mocked as a failed experiment and has now ended up being co-opted by the largest banks in the world. The idea here is for the digital country to amass such economic leverage that it cannot be ignored, as is what happens to micronations and regions trying to cede from the mainland. This is indeed a strong argument and what could make something likes this possible.

Once the new digital country amasses certain wealth, maybe even in a specific sector that the digital features of the country make the economies of scale work better, it is able to trade with other “real” countries, and therefore negotiate its recognition as a sovereign country. I believe that it is only at this point that a move to owning physical territory and holdings is possible. This is the way many smaller countries manage to economically compete with other geographically larger countries. In a world where a large amount of land means more natural resources, smaller countries tend to find niches that make them attractive to future citizens (therefore, human resources), and to companies trying to invest. By allowing the digital country to find a highly specific niche which it can offer to other countries, this will start a process for eventual ‘acceptance’ of this new type of country. As a result of this economic leverage, the new digital country would also be able to start a process such as owning charter cities, allowing it to test its previous digital-only governance on land, and therefore making it real to other countries.

Indeed, “real” successful countries have had their sovereignty recognised on the world stage over a number of years, where they usually start by creating a precedent – one thing leading to the next, joining different fora and international organisations, until the country becomes an integral part of the world order and eventually a member of the United Nations.